Through June 30, 2013, at the Oakland Museum

|

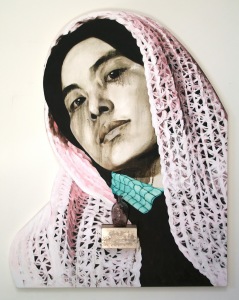

| Daughter of the Revolution, 1993 courtesy museumca.org |

It took me a while to warm to Hung Liu’s art. Not to the artist herself. As soon as you meet her, she pulls you in. Her combination of humor and seriousness wins you over. She uses her English-as-a-second-language as a device to outmaneuver you. Hung Liu understands how almost everything can become its opposite.

No, it took me a while to warm to the overwhelmingly representational imagery in Hung Liu’s paintings. But like so much art, traditional or conceptual, you just have to give it time.

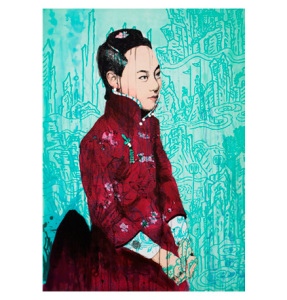

Hung Liu was educated at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. She moved to the United States in 1984 and graduated from UC San Diego in 1986. She draws on her social realist training in China and turns it on its head. When I look at her painting Chinese Profile III, I focus on the old woman’s hand and see a stunning abstract painting. When I rejoin the vignette to the whole, it is, once again, a beautifully rendered hand. Hung is painting realistically and abstractly simultaneously. By redeploying the realistic technique of propagandistic art, she celebrates the individual. Each person in Hung’s world asks the viewer to think about them, their life, their woes, their joy, their unique humanity.

|

| Chinese Profile III, 1998 courtesy museumca.org |

I had never seen her small paintings or photographs. In China, fearing persecution by government authorities, she had to create these works out of sight. This is why the series of small paintings are called My Secret Freedom. Art was her freedom symbolically and, eventually, literally. The curator has placed these pieces in a small side gallery that reminds the viewer that this art could not be created in the open. In contrast to the rest of the exhibition, they are small and intimate, like a treasure that has just been discovered. It is no wonder that after she moved to the United States, Hung Liu’s canvases came to be so large and to boldly command the viewer’s attention. Freedom needs to be seen and heard.

|

| Village Photograph 8 courtesy hungliu.com |

|

| My Secret Freedom 11 courtesy hungliu.com |

|

| To Live courtesy hungliu.com |

She returns to the intimate scale when she records her mother’s belongings after she passed away. These paintings are also tucked away in another side gallery. Be sure to see them.

In a long, horizontal piece like Hua Gang (Flower Ridge), the starving men contrast with beautiful pink flowers. We know these men are likely to be dead, but the viewer can remember each unique being surrounded with beauty. Other reviewers have remarked on Hung’s drip technique, which I think of as evidence of rebellion against the strict social realist training. And as tears.

She remembers the dispossessed. Many pieces are of women in oppressive conditions, whether they are forced to serve as laborers or prostitutes or simply to suffer the restriction of bound feet. One of the most stunning works is Mu Nu (Mother and Daughter), with more shades of gray than I ever imagined.

|

| Mu Nu (Mother and Daughter), 1997 courtesy museumca.org |

|

| Shan — Mountain, 2012 courtesy paulsonbottpress.com |

The painting that took my breath away was September 2001, where a squawking bird and a child symbolize an unwilling plane and an innocent tower. The fruit, flowers, and feathers of the crown are interdependent. One way to process the enormity of the tragedy of 9/11 is to focus on one child and on the beauty of nature. Despite the preponderance of drips, the fantastic imagery rings clear. Every life matters.

|

| September, 2001 courtesy hungliu.com |

For further information:

http://www.hungliu.com/

http://www.museumca.org/gallery/summoning-ghosts-art-hung-liu

http://www.paulsonbottpress.com/artists/liu_hung/liu.html