This is a slightly edited version of my comments at the Celebration of Life service for my sister Connie Caldwell held on December 29, 2019

As I stand here with so many faces I’ve known for so long and so many faces I have never seen, let me say that I am deeply proud of my sister and the life she lived. The greatest comfort in this time is love. We are surrounded by family and friends who knew Connie and our family, in some cases since the beginning.

Shortly before my sister passed away, she told me that she had perceived us three children as triplets of a kind. She was referring to her feeling that, because she was ill so much as a child and stayed home, she advanced academically but had not kept up with her peers socially and was more aligned with her younger twin brothers. I was astounded. I had never thought of this before. What else had we never talked about?

In the weeks following her death, people wrote to me about her, and I was reminded that in so many ways, I didn’t fully know her. And yet my brother and I have known her longer than anybody here. It is because of this that we have the privilege of speaking to you. I hope my few words help outline a background for the person you knew.

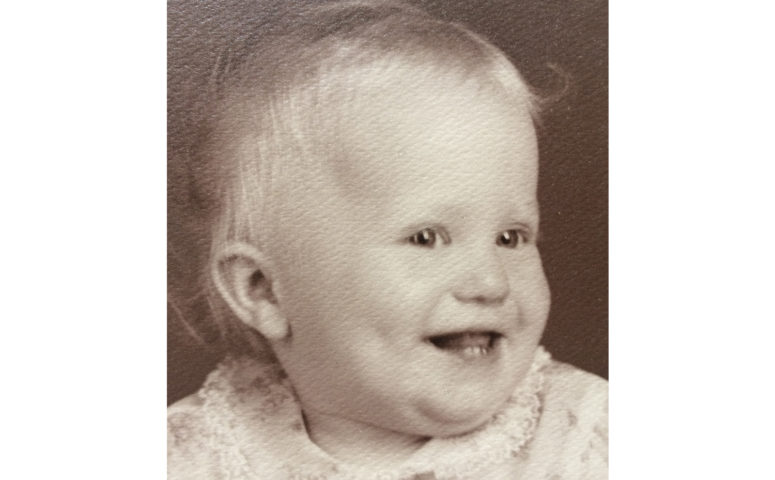

Constance Jeanne Caldwell was born on July 9, 1956, and passed away November 19, 2019. She was tenacious. Much of her young life was a struggle. Just before my brother and I were born, when she was two years old, she suffered a serious bout of bronchitis and was left with severe asthma, which affected her entire life, but especially her childhood. Often, she was unable to breathe, and the doctor would come out in the middle of the night. As a child, she had to stay home from school much of the time. Our mother, an educator, worked with her so she would not fall behind. Indeed, she ended up far ahead and always achieved high marks. But she was very short, with poor eyesight and funny looking teeth. She was an outsider. This was hard, but I think it also gave her an inner strength.

As kids, both of us drew a great deal in our spare time, and she was able to depict, with great accuracy, children with all kinds of disabilities. She had a story for each one. Connie was literally drawing her future of care.

Although our mother cared for and educated Connie, she didn’t quite get her. On the other hand, our father doted on her and forgave her impatience and her temper, perhaps because he was also quick to anger. Early on, she showed all kinds of artistic aptitude in addition to drawing, with the organ, guitar, and weaving, yet she was shy. He encouraged her in all these pursuits.

In junior high school, she became friends with another young woman; her name was Sharon McCorkell. Her father was a Methodist minister. At the time, I didn’t know that you got paid to do that work.

Together, Sharon and Connie built a wood model of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre for a school project. I asked Sharon about that endeavor, and she told me that they used a handsaw borrowed from her father and that Connie would give her tips on how to let the saw teeth ride in the groove and to not force the teeth—things she’d learned from our father. What they found was a shared sense of responsibility to help build a better world. In junior high school! Sharon also said that Connie laughed at her jokes, which I suspect was key.

After junior high, Sharon’s father was transferred from a congregation in Richmond to one in Alameda. Despite the distance, Sharon and Connie remained good friends. After high school, both of them got into UC Santa Cruz and became roommates at Kresge College.

When I was a junior and senior in high school, I went to visit Connie often in those dorms. I was drawn to both the architecture and ambiance of the place. Some of my happiest memories were the first tastes of freedom found there. We grew up in a super-organized and somewhat rigid household. To sit naked in a sauna with a bunch of college freshmen was the liberation we were both looking for. I remember sunning without any clothes on the lawn and the smell of marijuana in the air. It was the tail end of hippiedom, and we were breathing its last magical fumes.

During that second year, Connie and Sharon became partners. Santa Cruz must have provided a safe place. I wouldn’t say my sister and her then partner were the alumni cheering type, but they became loyal slugs! (That’s the UC Santa Cruz mascot.)

My sister was both fearful and fearless. She saved her energy for what mattered. It was hard to imagine my shy sister planning trips across the country to interview for medical school. But she did. I think it was relief when she got into the joint UC San Francisco/UC Berkeley program, where you got a master of public health and then a doctor of medicine degree. She chose pediatrics as her specialty because she could relate so well to the challenges of children.

Eventually, her career would pivot towards public health. My sister heard what Robert Coles called “The Call of Service.” Service was in her DNA. I imagine she had to wrestle with bureaucracy in her work, but again, if it served the goal, she would navigate. Emails praising her have come to me from people I don’t know. Of course, I knew she was a doctor, but I didn’t know her as a doctor. These stories, your stories, are very special. They fill in the blanks.

Over a decade ago, she decided to convert to Judaism. This was hard for me to understand. Growing up, she seemed the most devout of agnostics. Now I think her spiritual quest and her call to service became woven together. She found community and joy at her temples in Davis and here in Aptos. They were part and parcel of her path.

As some of you know, she was also very interested in fiber arts. Again, she didn’t go halfway. She raised the sheep that would produce the wool that would be carded and cleaned, spun, and knit, or woven. Watching a professional shearer buzzing a sheep is something I would never have experienced if it weren’t for my sister and Sharon! Working in fiber arts is also meditative, and I see that as part of her practice as well.

I knew my sister well in intervals. When we were kids growing up, her first years at UC Santa Cruz, in San Francisco, and when she lived nearby on Stuart Street in Berkeley when Maya was born. Perhaps less so after I moved to Los Angeles briefly and then returned to the Bay Area focused with my own career. What I do know is that she was a devoted physician, mother, and spouse.

As the years went on, my sister and I shared similar progressive politics. We were often at the same protests, just in different cities. Connie advocated for gay and lesbian rights, women’s rights, and all human rights. This was consistent with her worldview.

Perhaps our lives would have overlapped more as we both moved towards retirement and pursued our interests outside of work. Connie Caldwell was one of the most focused people I’ve ever met. She lived a life of purpose and overcame many, many obstacles. Her path was clear. She was engaged in a kind of radical love. I mean it in the way I think Dorothy Day meant it: every person is worthy of love and assistance.

Connie lived her own model of kindness. You may not change the entire world. But you try and help and love the people you find along the way. She didn’t sit around and chat about it; she went out and did it.

Love is what remains.